Insect Wings

Insects use their wings to accomplish feats that pilots can only dream of. Their aerodynamic acrobatics have fascinated scientists for years, and the old conviction that bumblebees should not be able to fly has finally been undeniably dispelled. Recent studies in the area of fluid aerodynamics have shed a significant amount of light on insect wings and flight.

Negative

Negative

Positive

Positive

Positive

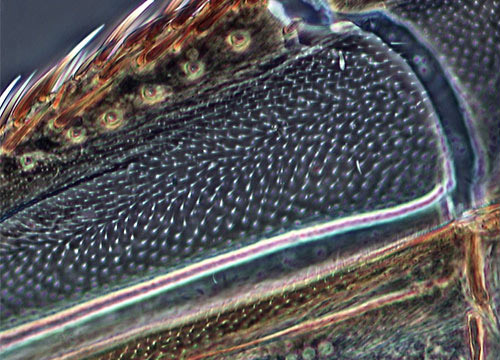

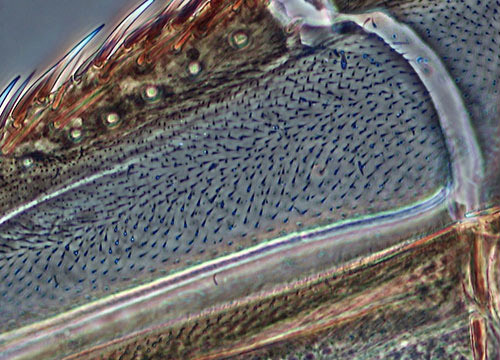

Insect wings are thought to have evolved from a gill-like thoracic segment present in early insects. Their essential material is a thin membrane covered with hair-like projections and supported by blood-filled veins. The leading edge of the wing is much stronger and stiffer than other regions of the wing, which are more elastic and capable of twisting. The areas between the veins arch up, curve down, angle and bend in a multiplicity of architectures.

Negative

Energy is transferred to the wings from powerful muscles within the insect's thorax, but like sails on boats, wings largely depend on the arrangement of their supporting framework. During flight, the wings become distorted by the shifting forces acting upon them, but in a useful and efficient way. Accompanied by complex wing movements, which are often in a figure-eight pattern, wing distortion provides insects with tremendous mid-air maneuverability. In hopes of developing something of great practical use, engineers have been trying to replicate the intricate wing structure and motions of insects for many years. If their attempts prove successful, the advances in flight technology could be phenomenal.