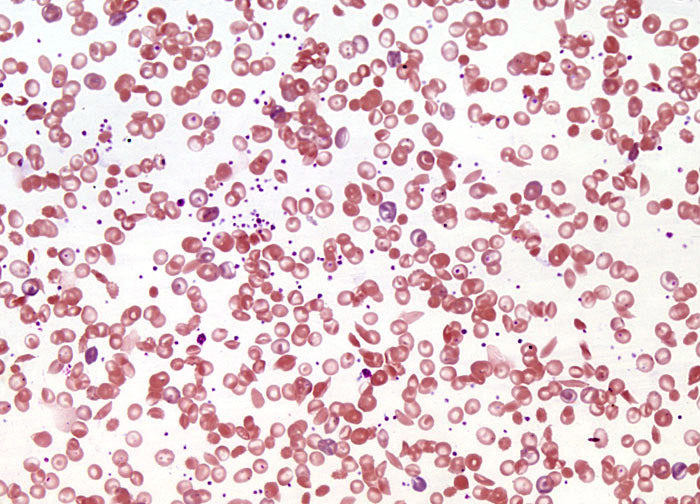

Sickle Cell Anemia at 20x Magnification

Early twentieth-century descriptions of sickle cell anemia in Western literature noted that sickling was related to low levels of oxygen, and before mid-century Linus Pauling and Harvey Itano demonstrated through protein electrophoresis that the hemoglobin of patients with the disease is different than that of normal individuals. In the subsequent decades, a more complete understanding of the disease was culled. According to modern medicine, sickle cell anemia is caused by a point mutation in one nucleotide within the sequence of 438 bases coding for the hemoglobin beta chain. A shift in the seventeenth nucleotide from a thymine base to an adenine base in the DNA of genes encoding hemoglobin causes a switch in the sixth amino acid, from glutamic acid to valine, in people with sickle cell anemia. The change of this one amino acid results in hemoglobin (generally referred to as hemoglobin S) that responds to oxygen deficiency by stacking into filaments and clustering in red blood cells containing the mutated protein in such a way that their shape is distorted. Initially, cells experiencing the distortion, or sickling, can resume their normal shape when they are reintroduced to oxygen. However, over time, they lose this ability and the sickle shape becomes permanent.